[ad_1]

One of the main challenges with immunotherapies is the range in their effectiveness. While in some people tumors shrink or even disappear others people have no response at all. Researchers have been trying to understand this disparity for some time.

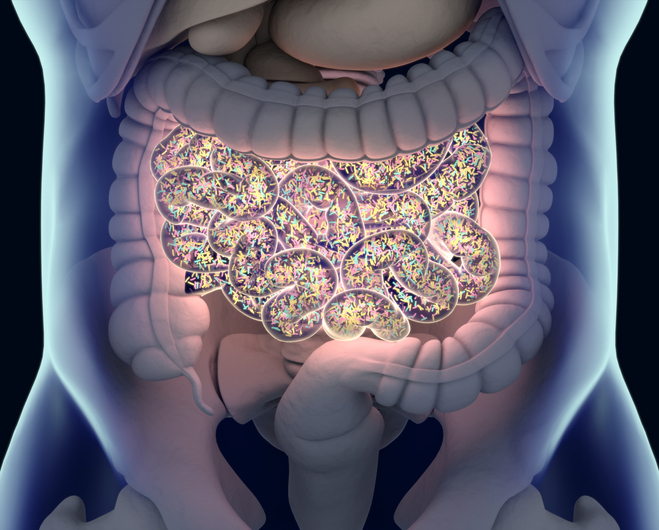

The gut microbiome has emerged as one possible factor. Gut microbes are thought to play a role in the body’s immune response. Early studies found that modifying the gut microbiome may improve the odds of tumor response to immunotherapy. But this phenomenon is not well studied.

Researchers led by Giorgio Trinchieri of NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI) and Carrie Daniel and Jennifer Wargo from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center examined the links between diet, gut microbes, and response to immunotherapy in 128 people with melanoma.

They assessed fecal microbiota profiles, dietary habits, and commercially available probiotic supplement use in melanoma patients and performed preclinical studies in parallel.

The participants reported their eating patterns and any use of probiotic supplements in the month before receiving immunotherapy. The team also took stool samples to analyze participants’ gut microbiomes. Results were published last month in Science.

People who reported higher fiber intake, which is believed to promote healthy gut microbes, had better responses to treatment overall. After adjusting for other factors, the researchers found that every 5-gram increase in daily fiber intake corresponded to a 30% lower risk of cancer progression or death.

Probiotics didn’t appear to improve survival. In fact, the data suggested they might lower survival.

Higher dietary fiber was linked to improved progression-free survival in the 128 patients studied. The most noticeable benefits were seen in patients with “sufficient” fiber intake and no probiotic use.

The researchers reported that “Findings were recapitulated in preclinical models, which demonstrated impaired treatment response to anti–programmed cell death 1 (anti–PD-1)–based therapy in mice receiving a low-fiber diet or probiotics, with a lower frequency of interferon-γ–positive cytotoxic T cells in the tumor microenvironment.

The team studied mice to confirm these findings. Mice with melanoma tumors were treated with immunotherapy. Those fed a high-fiber diet had slower tumor growth than those fed a fiber-poor diet. Mice fed the high-fiber diet also had more anticancer immune cells in their tumors. In contrast, diet didn’t affect tumor growth in mice without any gut bacteria.

The team also found that mice given probiotics had a reduced response to immunotherapy and developed larger tumors than control mice.

“Many factors can affect the ability of a patient with melanoma to respond to immunotherapy,” Trinchieri says. “However, from these data, the microbiota seems to be one of the dominant factors. The data also suggest that it’s probably better for people with cancer receiving immunotherapy not to use commercially available probiotics.”

Larger studies including people with other cancer types are needed to more fully understand the relationship between diet, microbes, and immunotherapy. A clinical trial is now testing the effect of diet on the gut microbiome and immunotherapy outcomes in people with melanoma.

[ad_2]